Rusalka

How much of yourself can you sacrifice for love?

-

DATES:Sept 27 — Nov 12 2025

-

STAGE:Main stage

-

RUNNING TIME:approx. 3 hrs 5 mins incl. 2 intervals

-

LANGUAGE:Czech, Swedish surtitles

Czech fairy tale opera on the theme of an unhappily in love water nymph — a mermaid for our time — signed by the master Dvořák.

This performance is not currently playing

Subscribe to our newsletter for information about upcoming seasons, ticket sales and possible re-runs of performances. You can search for previous performances in the Archive.

Subscribe to the newsletter →This story about the unrequited love of a water nymph has been told in many different forms throughout the ages. Now Dvořák’s Late-Romantic masterpiece Rusalka is finally on the Royal Swedish Opera programme! The director, Netia Jones, has taken the Czech opera from 1901 and placed it in our own appearance-obsessed era. An opulent production in cooperation with the Irish National Opera and Nouvel Opéra Fribourg.

-

Act 1

-

Interval

-

Act 2

-

Interval

-

Act 3

Read more about Rusalka

-

Synopsis

ACT I

The water nymph Rusalka has fallen in love with a human—the Prince—when he came to swim in her lake. Now she wants to become human herself and live on land to be with him. Rusalka’s father, the Water Sprite, is horrified and tells her that humans are evil and full of sin. When Rusalka insists, claiming they are full of love, he says she will have to get help from Ježibaba. Rusalka calls on the moon to tell the Prince of her love. Ježibaba arrives and agrees to turn Rusalka into a human—but warns her that if she doesn’t find love she will be damned and the man she loves will die. Also, by becoming mortal, she will lose her power of speech. Convinced that her feelings for the Prince can overcome all spells, Rusalka agrees and Ježibaba gives her a potion to drink. As dawn breaks, the Prince appears with a hunting party and finds Rusalka by the lake. Even though she won’t speak to him, he is captivated by her beauty and leads her away to his castle. From the lake, the voices of the Water Sprite and the other water nymphs are heard, mourning the loss of Rusalka.

ACT IIAt the Prince’s castle, the Gamekeeper and the Kitchen Boy talk about the approaching wedding of the Prince and his strange new bride, whose name nobody knows. The Prince enters with Rusalka. He wonders why she is so cold toward him but remains determined to win her. A Foreign Princess, who has come for the wedding, mocks Rusalka’s silence and reproaches the Prince for ignoring his guests. The Prince sends Rusalka away to dress for the ball and escorts the Princess into the castle for the beginning of the festivities.

In the deserted garden, the Water Sprite appears from the pool. Rusalka, who has become more and more intimidated by her surroundings, rushes from the castle in tears. Suddenly recovering her voice, she begs her father to help her, telling him that the Prince no longer loves her. The Prince and the Princess come into the garden, and the Prince confesses his love for her. When Rusalka intervenes, rushing into his arms, he rejects her. The Water Sprite warns the Prince of the fate that awaits him, then disappears into the pool with Rusalka. The Prince asks the Princess for help but she ridicules him and tells him to follow his bride into hell.

ACT III

Rusalka waits by the lake once again, lamenting her fate. Ježibaba appears and mocks her, then hands her a knife and explains that there is a way to save herself: she must kill the Prince. Rusalka refuses, throwing the weapon into the water. When her sisters reject her as well, she sinks into the lake in despair. The wood nymphs enter, singing and dancing, but when the Water Sprite explains to them what has happened to Rusalka, they fall silent and disappear.

The Prince, desperate and half crazy with remorse, emerges from the forest, looking for Rusalka and calling out for her to return to him. She appears from the water, reproaching him for his infidelity, and explains that now a kiss from her would kill him. Accepting his destiny, he asks her to kiss him to give him peace. She does, and he dies in her arms.

-

Interview with director Netia Jones

Finally, 124 years after the world premiere in 1901, Antonín Dvořák’s masterpiece reaches the Royal Swedish Opera. Director Netia Jones has a lot to say about the piece.

Netia Jones is a director, designer and video artist working internationally in opera, theatre, concerts and immersive installation projects. In 2024, she was appointed to the newly created position of Associate Director of The Royal Opera in London.

The new production of Rusalka is co-production between the Royal Swedish Opera, Irish National Opera and Nouvel Opéra Fribourg. Netia Jones is passionate about the project:

- It is a wonderful piece that I had been thinking about, long before receiving the call and being asked “would you like to do a Rusalka?”. Particularly because we are reconsidering these depictions of women, both as ideas of a mermaid or a siren or a witch – these archetypes that have been quite harmful – and have been often unquestioned. The time now is actually to interrogate these characters. And really see how that has affected the way we have behaved with each other.

For Netia Jones, interrogating the content is an essential part of the process of presenting operas.

- We are working with an artform that was created 400 years ago, and if we don’t interrogate the content, we are just going to carry over all of the prejudices and the world views and the imbalances that were very much a part of societies then. If we want to continue in a productive way, I feel that it is absolutely essential to interrogate it. I believe that opera shouldn’t be a museum-like art form – I think it should live and breathe in the here and now, and respond to the things that we are talking about and dealing with in the world today. So, funnily enough, a fairytale, which would seem very old fashioned, is actually one of the more easy things to translate into a modern imagination. Because there is a very wide open interpretative space, so you can easily imagine your own world within the fairytale.

When Jaroslav Kvapil wrote the libretto for Rusalka, he combined two very different elements. One part was the story of the heartbroken water spirit, made famous by Freidrich de la Motte Fouqué in Undine (1811) and even more famous in H C Andersen’s The Little Mermaid (1837). Another part was the Slavic folklore figure of a rusalka, a female wood sprite living close to water. But a rusalka is very far from sweet and tender mermaid.

- Rusalki are powerful, dark, and full of energy. They traditionally had long matted crazy hair, climbed up and down trees, were full of power. And this is something that I find really spectacularly interesting, and also a little bit heartbreaking, because it is something that we see so much in girls now. They have this incredible power and self-confidence and strength, until about the age of eleven, when they are destroyed completely by society. Because they become self-conscious, and they become aware of boys, and they become aware of themselves.

In the main character of Rusalka, Netia Jones recognizes a young girl with huge ambitions.

- She longs to exist outside of the very limited world which she is in. Her father, who has been fine in this rather limited world, feels slightly threatened by his daughter wanting to leave it – but also very sad and upset by that. There is an incredible truth in the relationship between the father and the daughter, that is really profound from both points of view – both from being the parent of a young girl, and from having been a young girl. The struggle between them also feels very true. And then, obviously, we have the unfortunate truth of a very attractive charming, successful and rich young man who has a very short attention span with regard to women. He absolute needs to seduce Rusalka, but then very quickly he is bored of her and then he himself is seduced by this glamorous foreign princess. That is a triangle which is extremely painful and extremely recognizable. That happens all the time, not just in stories – in real life.

- Rusalka is so interesting as an operatic figure. I think there is something very original in the treatment of her. We often see, in 19th century opera, doomed women. There are plenty of women who have to suffer and die. But the ending of Rusalka isn’t quite like that. It’s quite subversive in that way.

The different versions of this story have different endings. In Undine, the female water spirit-turned-human kills her lover in the end, after he has left her for another woman. In The Little Mermaid, the heartbroken mermaid cannot bring herself to kill the prince, instead she kills herself. In Rusalka, she is heartbroken after the prince has left her for another woman, but the difference here is that the prince regrets his choice and comes back for Rusalka – even if he knows that a kiss from her will lead to his death.

- I think it’s an incredibly interesting question mark that Dvořák and Kvapil leave at the end. There are different traditions in the way this story is told. We have the »Danish Rusalka« who is jilted by the prince and who dies of sadness; then there is the »Scandinavian Rusalka« who is jilted by the prince and kills the prince and is sad; and then there is the »Russian Rusalka« who is jilted by the prince, kills the prince and then dances on his grave. I think the shades of what this character might be like is so interesting to explore.

What happens to Rusalka after the opera has ended is an open question. Maybe she dies, maybe she goes on living but will be lonely forever, but in any case, it is a tragic story.

- Yes. It is tragic because leaving childhood is a tragedy. From innocence to experience, it is a Rubicon that you cross and you can’t go back.

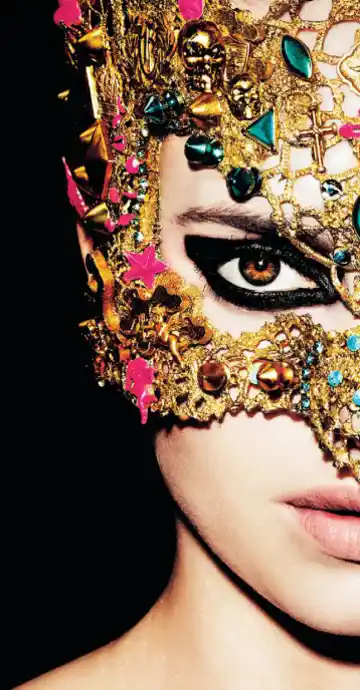

The witch, Ježibaba, is in your version working in a plastic surgery clinic. Does this change the story a lot?

- No, we are following the libretto, if you think of what is being said – the idea is that she can create things that can create transformation. But we have translated the idea of how she does transformations into this idea of surgery. Because what we are seeing increasingly, with younger and younger women, is that a physical transformation is required in order to be attractive or acceptable. So this extraordinary shocking exponential rise of plastic surgery, botox, all of these things are transformations. So Ježibaba is literally doing what the libretto says: she is transforming one thing into another. The idea of her having a clinic is not more complicated than if she had potions like a typical witch. I mean, what is medicine if not potions?

The other woman, the Foreign Princess, she is also interesting. How do you look at her?

- She is so real. She is a woman of the world – a very sophisticated, glamorous, confident woman – who is the absolute polar opposite of Rusalka who is quite literally, metaphorically, a fish out of water. Rusalka is so uncomfortable in this high society, this high affluent environment. Rusalka is effectively a child, she is so young, so inexperienced. I think we all have had those moments of being really out of our depths. Like a country girl going to town. It’s an archetypal character. It’s like Eugene Onegin – the two women in Rusalka are like the two versions of Tatiana in that opera, the early Tatiana and the late Tatiana.

Do you think that the Foreign Princess is older than Rusalka?

- Yeah, I think she must be older than Rusalka. But even if she doesn’t have to be awfully lot older, she is awfully lot more experienced than her. She is a very experienced person and a bit jaded. You get the sense of her being a bit tired of life. Like the prince, you get the feeling that things have come to her very easily, she hasn’t had to fight for anything. So she has that slight burden of boredom, which comes with great privilege.

- I think she has a very interesting first fatal flaw which is jealousy. So she behaves monstrously to Rusalka, because you sense straight away that she feels miffed. Maybe it is because Rusalka is so pure and young, or maybe it is simply the fact that she is so entitled that not having enough attention makes her angry enough to behave badly.

What do you think of Dvořák as an opera composer?

- Dvořák is very confident. This opera is clearly the work of somebody who has achieved a lot. It has a superb theatricality. And also, stunning music. It’s not just about one big aria – there are endless moments of vivid drama, beauty and pathos. It has a very good flow, it’s very bold. To have a protagonist, a lead character, who is silent for a whole act – such a bold move. Rusalka feels very confidently made.

- Even if it is a tragic story, with profound truths in it, I really also hope is that the opera will be entertaining – so fun in a way that a fairytale can be. We have the moments of visual excess, the extraordinary ballroom scene, which is the kind of apex of the opera, this huge moment of brilliant music and great extravagance. Dvořák has shaped this piece so well, the audience is taken on this exhilarating journey in some of the most beautiful music ever written. There is just so much to enjoy.

Nicholas Ringskog Ferrada-Noli

EDITOR AT THE ROYAL SWEDISH OPERA

Introductions & talks

In connection with the premiere on September 27, all ticket holders are welcome to a free talk in the Golden Foyer at 6 p.m. when the Opera's dramaturge Katarina Aronsson meets director Netia Jones in a conversation about Rusalka. On other performance days, a free introduction to the piece takes place in the Golden Foyer 45 minutes before the performance starts!

-

Cast

-

-

Music & creative team

Music Antonín Dvořák

LibrettoJaroslav Kvapil

Conductors Alan Gilbert/Case Scaglione

Director, scenography, video and costumes Netia Jones

Light Lotta Hammarstrand

Dramaturge Katarina Aronsson

Choreography Jessica Kennedy

Cast subject to change.

Your visit to the Opera

Frequesntly asked questions

-

At what time do I have to be at the Opera before the performance?

We recommend that you arrive at least half an hour before the performance begins. If you can arrive earlier, it's even better: 45 minutes before the start of the performance, there is a free audience introduction in the Golden Foyer - an excellent way to approach the performance! Please note that once the performance has started, no one will be allowed into the hall until after the first intermission.

-

It's my first time at the Opera - what do I do?

We have put together some useful tips for your visit. Otherwise, our best advice is to arrive on time - discover the Opera House, leave your coat in the cloakroom, eat or drink something. AND, ask our ushers - they'll be happy to help! Outerwear and bags should be left in the cloakroom for safety and evacuation reasons.

-

Can my ticket be rebooked or cancelled if I or someone in my party is ill?

You can rebook tickets yourself on the website up to 24 hours before the start of the performance within the the current season. Tickets cannot be cancelled (read more in our general terms and conditions).

-

Can you eat and drink at the Opera?

Of course you can! Our partner Restaurang Grodan is on the ground floor facing Strömgatan - take the opportunity to book a table ahead of your visit! Each floor also has a service with drinks and snacks, at the stalls' café there is a slightly larger selection. We advice you to pre-book the intermission service so it is ready and waiting for you during the interval!

Don't miss a single beat!

Did you know that our newsletter subscribers always get the latest information first? Stay up to date on upcoming productions, ticket releases and other news.

Subscribe to our newsletter →